If you teach multilingual classes, you have a ready-made ELF environment to exploit! The learners come from different first-language backgrounds, so are using English together as their lingua franca (language for communication).

In our experience, the multilingual classroom environment often reveals just how problematic pronunciation can be for ELF interaction. For example, students whose first language is Chinese and students whose first language is French may sometimes struggle to understand each other.

This post focuses on one way of doing a needs analysis with such a group, which will help you determine what areas of pronunciation to prioritise during their course.

Update, Jan 2015: there is now also a video showing this kind of needs analysis in action here.

Note that even if your students do not all have the same goals (e.g. outside class hours, some use English mainly as a lingua franca, but others use English with native speakers, and some students from both groups may want to sound like a native speaker), the use of English within the multilingual classroom is indisputably ELF.

Following a bespoke syllabus based on the needs analysis described below will therefore be a useful starting point for all students, as nobody would need to ‘unlearn’ anything (everything in the LFC also features in native English speaking accents) and it might make classroom practice easier in the short-term.

How to do it

1. Prepare some sentences

You need one sentence per student. Make sure you number them (this will be helpful later).

They should be not too short, not too long (about 12-15 words should do), and it doesn’t matter if there are some new/unknown words – the students can check the pronunciation of these with you later (see step 2, below).

Ideally, each sentence would include a wide variety of features from the Lingua Franca Core. Realistically, however, you might be following a coursebook and might not have time for/access to many supplementary materials. So you could just re-type a list of sentences from a coursebook exercise (e.g. sentences from a speaking/vocabulary task).

In the future, we hope to post some sample sentences here for this purpose. In the meantime, you’ll have to make do with what you’ve got in your coursebook. An example is given below.

From New Total English Upper-Intermediate Students’ Book, 2011, pg. 77

There’s also a potential advantage to using sentences from a coursebook like in the example above – they’re all connected to the same topic. So after doing your pronunciation needs analysis, you could allow students some free speaking practice using these sentences (e.g. talk about which ones are true for you).

Note: if you want to use the sentences for free speaking practice as well as your ELF pronunciation needs analysis, it’s important to do the pronunciation part first. This is so that the students are relying only on pronunciation (not on context) to understand what each other says, which is what you want to focus on.

Why re-type the sentences? Well, you could just enlarge them on the photocopier, but I think it’s worth the effort to type them out because you can leave space between each one, then print two copies: one to cut up and give to the students (1 sentence each), and one for you to write notes on (in the space between each sentence) later, during the lesson.

2. Student-student dictation (preparation)

Assign one sentence to each student, or let them choose at random. Explain that they’re going to dictate their sentence to the other students, and that you’re going to listen carefully to everybody’s pronunciation so that you can prepare pronunciation priorities for future lessons. (This relieves the stress of reading aloud somewhat – they know there’s a good reason for it and it’s not a test, but is truly a needs analysis.)

Give the students about 5 minutes to prepare their sentences for dictation. They can mark phonemes, stress, appropriate points to pause, ask you about any words they don’t know, etc.

3. Student-student dictation (performance)

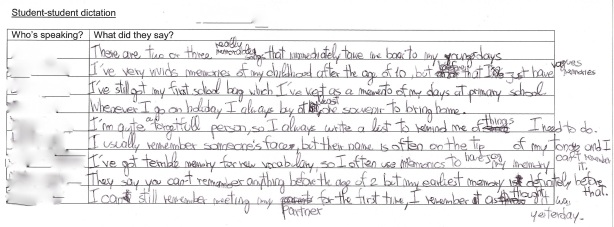

Distribute a dictation table to each student. There should be one row fewer than the number of students in the class (e.g. 10 students = 9 rows in the table). This is because each student will only write down the other students’ sentences, not his/her own.

You can download a sample here, which is based on a class of 9 students and looks like this when printed out:

As you’ve numbered the sentences (see step 1, above), you can easily decide who goes first, second, etc., without any student feeling singled out to start.

One by one, each student reads his/her sentence 2 times only. The other students write his/her name in their tables and in the ‘What did they say?’ column, they write down what the student dictates.

(You may need to remind them that it’s a dictation exercise, so they should try to speak at reasonably natural speed without going so quickly that nobody can keep up!)

If the other students are not sure they heard correctly, they can leave a gap and ask the speaker to clarify that part after they’ve done their 2 normal readings of the sentence.

For a class of 10 students, this stage alone could easily take 20-30 minutes, so allow plenty of time.

This is how one student’s table might look when finished (I’ve anonymised it, but you can see where they had written their classmates’ names in the left-hand column):

While they’re doing this, you are, of course, also listening and making notes on how they pronounce their sentences. Here’s an example of how my paper looked during this particular session:

You can see that I’ve written anything and everything that I noticed during the dictation, regardless of whether it seemed to be problematic for other students or whether it was relevant to the LFC. (I could always choose to ignore some things later.) I just wanted to have as accurate a record of possible of how they had pronounced their sentences and how the other students (might have) understood them.

Of course, analysing in real-time like this will always be somewhat selective. If possible, you could record the students doing the dictation, but this might lead to you spending a long time after the lesson listening to it again and again – it depends how much time you can really dedicate to this task.

4. Analyse everything

After the dictation, collect the students’ notes and analyse what they had difficulty with. Specifically, this involves:

- comparing your notes with what they’ve written, to see if anything you thought was problematic actually did impede the other students’ understanding. What’s interesting is that many of the things I noted down in this example proved to have been unproblematic for the other students, as evidenced by their filled-in tables (which I collected afterwards). It just goes to show that teachers’ and/or native speakers’ (I myself fall into both categories) intuitions about what will be ‘problematic’ pronunciation are not always well-founded. So doing this kind of thorough analysis, instead of assuming what students will need to work on, is really valuable.

- comparing how one student’s dictated sentence was understood by all the other students. Sometimes you see commonality – for example, many of the students in the group illustrated above misheard “at least” as “a list” (in sentence 5), suggesting that they could not work out what made sense from the context of the rest of the sentence, and/or that the length distinction between the vowels in ‘list’ and ‘least’ is very important, and/or that the /t/ at the end of “at” was important to include clearly. Two interesting points arise here: (1) both of these last two pronunciation features are included in the LFC; and (2) you can see from the notes I took during the lesson (above) that this student correct his own pronunciation the second time around. When I looked at his fellow students’ dictation tables, I could see evidence of them having written “a list” the first time, then correcting it to “at least” the second time he read the sentence. This really helped my analysis, as I could see very clearly what the students had (mis)heard.

- comparing how one student heard all the other students’ sentences. I’ve noticed when doing this type of needs analysis that, just as some students generally struggle to make themselves understood to others, some students also have general difficulty understanding others. In the example above, one student in particular from my class of 10 stood out as having significant difficulty transcribing the others’ sentences. I found out later that he is dyslexic and finds listening and writing at the same time extremely difficult. In fact, he understood the others’ sentences quite well when he wasn’t forced to write them at the same time, but just listened and looked at the students’ faces. As soon as he tried to write their sentences down, however, he had multiple spelling mistakes and very messy notes in general. So do be careful with the conclusions you jump to when doing this type of analysis – not all difficulties are due to pronunciation.

5. Give students feedback

Technically, this step is optional – you did all that work primarily in order to devise a pronunciation syllabus for the course. But I tend to believe students are more motivated and more likely to improve when they have personal feedback and guidance on their strengths/weaknesses from the teacher.

To this end, I usually create a little blurb for each student to give them advice on their productive/receptive abilities and help them see the relevance of the pronunciation work I’ll be including in the rest of the course.

You can download here the feedback I gave to the students described in this post.

6. Make a list of priorities for the course

Analysing everything this thoroughly can take an hour or two, easily. But that’s time very well spent if you’re going to be teaching the group for even a few weeks. If you have them for a few months or a whole academic year, it’s definitely worth the effort.

While doing the analysis, you’ll start to notice patterns and things that occur frequently. Write all these down as you go, then compare them with the LFC. The resulting selection will form the basis of your productive pronunciation priorities for the course.

For example, from my analysis of the group detailed above, I decided to work on the following:

- /ŋ/

- short-long vowel contrasts

- consonants at the ends of words

- placement of nuclear stress

- common spelling patterns for vowel sounds (to help students be consistent in their pronunciation, instead of guessing randomly!)

You will also probably notice that some students need to develop their receptive abilities for particular accents of English. In the class I’ve used as my example here, this was evidently not problematic for most students. But if you have a student who struggles to understand the pronunciation of one other student in the group, e.g. the Spanish speaker (just for the sake of example), it’s worth noting this down. Providing you have a friendly and professional rapport with the group, you should be able to be quite open about this in future lessons — discuss what is characteristic of this student’s first language and how it affects his/her speech. Then the next time a Polish-speaking student (again, just for example) hears “the vest”, they might stop and consider that he/she might be saying “the best”.

You can also determine what accents prove difficult for your students to understand (whether native or non-native) through other in-class listening exercises. Look out for more guidance on this in future posts.

Pingback: Dictation in the ELF classroom | ELF Pronunciation

Pingback: Thank you, Harrogate! | ELF Pronunciation

Pingback: Thank you, London (and beyond)! | ELF Pronunciation

Pingback: Minimal pairs – ‘ELF priorities’ post 1 of 3 | ELF Pronunciation

Pingback: Nuclear stress – ‘ELF priorities’ post 2 of 3 | ELF Pronunciation

Pingback: Communication strategies – ‘ELF priorities’ post 3 of 3 | ELF Pronunciation

Thanks very much for this description – I am thinking about a pronunciation course for some fellow teachers and this will help enormously in the design of the needs analysis.

Hi Kristin

Thanks for your comment – glad you found it useful!

We’d love to hear from you later as to how the course is going. You can send us an email via the ‘contact’ link on this blog. Please do feel free to get in touch!

Laura

Pingback: How to do a needs analysis with a multilingual class (now with video!) | ELF Pronunciation

Pingback: Coming to IATEFL 2015? | ELF Pronunciation

Pingback: Thank you, Brighton! | ELF Pronunciation

Pingback: BELTA webinar: Teaching pronunciation and listening for ELF | ELF Pronunciation

Excellent ideas, and many thanks for providing the links to supplementary Word docs.